Three Ways to Create Healthier, Better Designed Communities

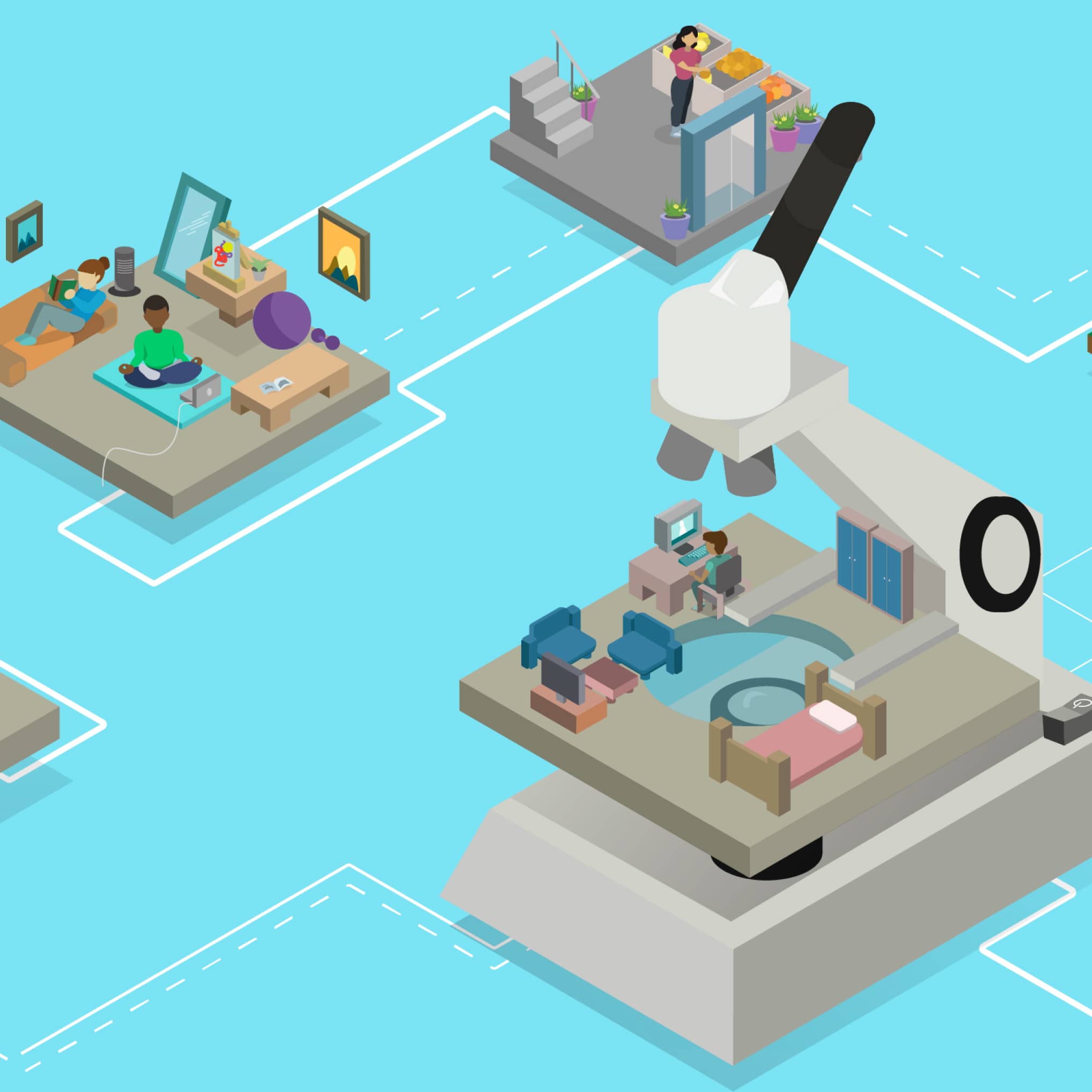

Public health is unquestionably impacted by the built environment. The design of buildings and cities can successfully facilitate or devastatingly hinder our ability to lead healthy lives. The way places are planned and operate impact how we access everything we need to survive, from healthy food and water to opportunities for socializing and getting around.

As a global climate crisis and pandemic simultaneously rage, discussing the relationship between public health and the built environment — and finding ways to improve it— has never been more urgent.

“When I think about the purpose of the public health field, I see that it’s also the purpose of architecture. Society has an interest to make sure we have conditions where people can be healthy,” said Dr. Richard Jackson, a pediatrician and Professor Emeritus of UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health.

When I think about the purpose of the public health field, I see that it’s also the purpose of architecture.

Jackson and a group of health, design and research professionals recently came together for a virtual panel discussion about how design equity can lead to healthier communities during HKS’ ESG in Design Celebration, the firm’s annual educational event series focusing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) topics.

The panel discussed how public health determinants are intertwined with the built environment, intensified by the effects of climate change and exclusionary development practices. As the globe warms, natural disasters threaten the safety of the structures we inhabit and human comfort indoors and outdoors. At the same time, community disinvestment and displacement exacerbate poverty, which leads to higher rates of depression, obesity, and other serious health problems.

In his introductory remarks, Jackson described UCLA’s BEWell initiative, which aims to implement best practices to overcome barriers the built environment can create for public health. BEWell stewards have worked to upgrade transit, infrastructure, and buildings to enhance mobility, air quality and accessibility on UCLA’s dense metropolitan campus. Jackson, who once served as director of the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health and as a board member of the American Institute of Architects, said that the success of such programs comes when communities embrace holistic sustainability practices, which improve health and reduce economic strain.

“Sustainability builds health and vice versa, and you can save money in the process,” he said.

The four panelists agreed that equitable and inclusive design processes are a pathway to improving community well-being and sustainability. Throughout the course of the conversation, they focused on three main strategies for designing healthier communities:

1 – Collaborate Meaningfully for More Active Change

“There are very clear indications and expectations of what the health outcomes will be for those who live in impoverished neighborhoods. Poorer environments lead to poor health outcomes,” said architect Lori Brown, a professor and Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Syracuse University’s School of Architecture.

Brown invites epidemiologists and public health scholars into her classes to illuminate facts like these and share real world examples of on-going social and health crises. She introduces design situations and problems that encourage students to think through how they, as designers, can work side by side with health professionals to improve community well-being.

In addition to collaborating with health care practitioners and researchers, Brown also advocates for political involvement as a mechanism for creating a healthier built environment. She encourages designers to work with local, state and federal government entities to influence fairer financial allocations for development projects, so that equity is embedded in them from the start.

“I think political engagement on the ground is really critical,” Brown said. “Our expertise needs to be a part of these conversations and a part of the decision-making bodies so we can hopefully create economic processes for more equitable outcomes.”

2 – Build Long-Term Trust for Better Health Outcomes

“Designers know the importance of the client relationship and the trust that it takes to craft it,” said HKS Senior Design Researcher Dr. Renae Mantooth, adding that when design professionals establish trusting relationships with building users in addition to clients, long term benefits for community health may be in store. Gaining trust in a design process, she said, is “really is about the people that are actually occupying and living in our spaces.”

Mantooth and her HKS colleagues design and implement longitudinal research studies that measure environmental satisfaction at educational institutions including elementary schools and universities. They have found that as much as the built environment impacts physical health by supporting mobility or providing access to nutritional food options, it also significantly influences mental health.

By seeking input from and building trust with students and staff, HKS designers and researchers like Mantooth make outcome-informed design decisions, creating places where healthy choices and social connections are easy to make, and access to the wellness benefits of nature is inherent.

“We’re starting to see a pattern. The more satisfied students are with their environments, they’re reporting lower levels of depression,” Mantooth said.

3 – Take Real Action for Improved Design in Communities

“If we’re going to engage directly with the people whose lives we want to improve, such as low-income communities, then we can only do that when we have the mandate or the power to show them action,” said Jeff Risom, Chief Innovation Officer at the Gehl, a design and research organization dedicated to enhancing the public realm.

Risom and his colleagues at Gehl work with communities around the globe to understand how they can be shaped for better physical, mental and social well-being. He said that traditionally, designers and clients haven’t always been great at following through on the input they receive through community engagement exercises, noting that the design community “has gotten pretty good at extracting information and talking to communities” but not “making good” on what is discussed.

To counteract potential obstacles to equitable design, Risom said Gehl has begun to request dedicated funds for long-term improvement from the cities and philanthropies the organization works with, not just funding for the engagements themselves.

“It’s a super tough challenge because cities [typically] have earmarked money,” he said, “But I think it’s up to us in the design world to actually demand that of our projects.”

Risom also believes that to expand equity to all development or improvement projects and realize broader public health outcomes, designers are responsible for bringing more architects and planners that represent historically disadvantaged or disinvested communities into the fold.

“We have to make sure that the folks who are designing can truly empathize with the communities they’re designing with and for,” Risom said.

Watch the full event recording here.

We have to make sure that the folks who are designing can truly empathize with the communities they’re designing with and for.