Outpatient Waiting Behaviours: A Cross-Cultural Pilot Study in the U.K. and China

What is the Aim

Challenge

Waiting is a well-established issue in health care. Patients wait for appointments, then wait again in waiting and exam rooms. It is a common problem often caused by insufficient resources, and in some cases, by inadequate organisation or timekeeping. These issues cannot be directly solved by architectural and interior design, but design could help mitigate the impacts of long waits. A patient’s wait time impacts their perception of the quality of care they receive as well as the perceived kindness and empathy of the staff. But that’s not all. Feeling like the waiting time is excessive can have the same effect on satisfaction rates as the actual wait time. The majority of available health care design research has been conducted in North America and Northern Europe. As designers, we have little choice but to apply this contextually specific research to a wide range of health care systems as well as cultural and demographic conditions. Some research may transfer and generate intended outcomes; however, much will not. There is currently little way to know what works and what doesn’t in contexts outside of those where the original study was conducted.

Aim

The study sought to discover what, if any, differences in waiting behaviours exist between two dramatically different cultures; China and the UK. Given the lack of existing information on this topic, it was critical to conduct a study that establishes whether our suspicions were correct so that further, broader and more in-depth research can be conducted in the future.

The majority of available health care design research has been conducted in North America and Northern Europe. As designers, we have little choice but to apply this contextually specific research to a wide range of health care systems.

What We did

Method

Outpatient waiting areas of three public health care facilities — two in Shanghai and one in the UK — were the locations of the study. A mixed-methods approach was used to maximise the qualitative and quantitative data gathering:

Behaviour Mapping

Sound Level Measurements

Photographic Surveys and Shadowing/Close Observation.

All methods were implemented over two days each at one facility in Shanghai and the UK facility. At the third facility, only Sound Level Measurements were recorded over one day.

What We Found

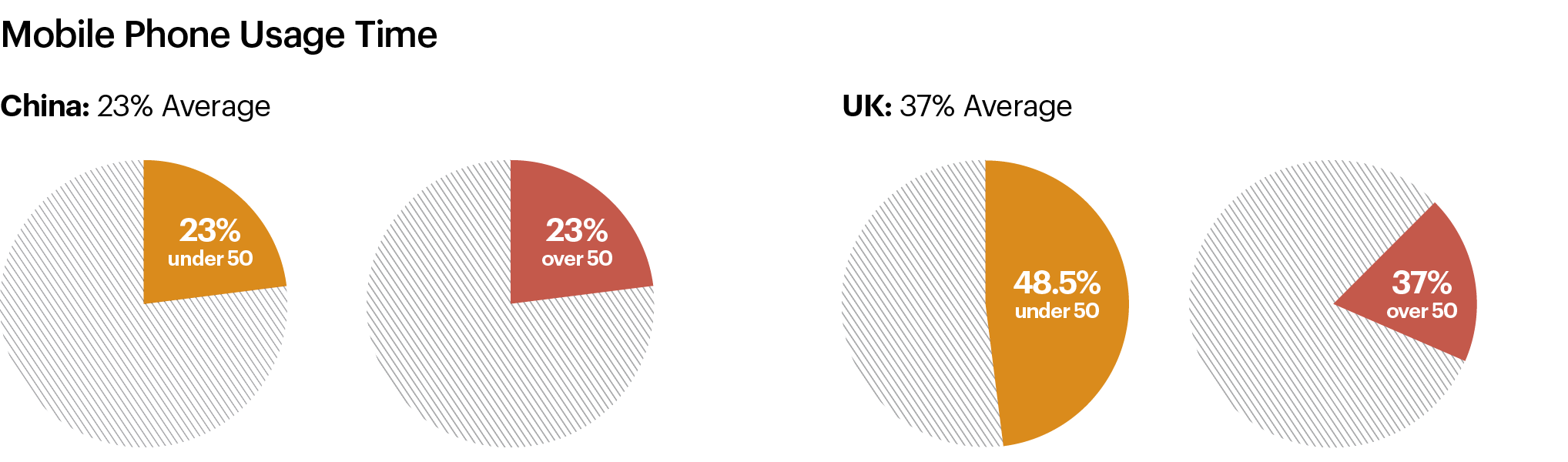

Phone usage was higher on average in China than the UK but more uniform across generations in the UK than in China. Therefore, phone usage should be considered a key behaviour to provide for and design for in both contexts. This could include phone charging points, quiet conversation areas or call booths. This would reduce some anxiety associated with phones losing battery power, disturbing phone calls made in the main waiting areas and the fear of missing being called for an appointment while trying to find a quiet spot for a phone call.

Sites in the UK and China could improve communication and information dissemination. Anxiety heightened when visitors did not know how long they would have to wait because of the impact an extended wait might have on childcare, work commitments or even parking tickets.

Improved information accuracy and dissemination with respect to waiting times is a key recommendation for both locations as this single move could reduce a lot of associated anxieties and impatient behaviours. Consideration should be given to hearing- and vision-impaired users as both facilities are in countries with significant aging populations.

Eating and drinking were far more common in the Chinese facilities than the UK facility. This occurred even though food and drink were provided in the waiting space in the UK in the form of vending machines while there was no food provision on the site of the Chinese facilities. To respond to the eating habits in the Chinese facility, we recommend that more food and drink options be provided on-site. Also, appropriate furniture —such as tables and chairs and not only bench seating —should be provided to accommodate well-established behaviour patterns.

A key finding was the differences in personal space and conversation preferences between users in China and the UK. In China, visitors were often conversational with others, whether they knew them or not. In the UK, visitors preferred to be separated from others in the waiting area who were not in their party. The seating in neither setting supported the preferred interaction levels of the visitors. This is a key behavioural difference and must be considered in all cultural settings.

What the Findings Mean

This study has established a toolkit of considerations that should be reviewed by all designers working on health care projects worldwide. These considerations should each be evaluated within the specific socio-cultural context of the project to ensure we deliver environments that are highly and accurately attuned to the needs of the users. This toolkit can be used as part of our proposals for projects outside of the cultural West to highlight our unique emphasis on understanding the nuances of local user groups’ preferences and needs within the health care environment.